Emotional Intelligence

According to Reeve (2009), emotions are short-lived,

subjective, and physiological phenomena that orchestrate how one reacts to both

personal and professional life events. Because business success relies on

effective interpersonal interactions, the method in which one understands,

adapts, and tolerates emotions directly influences outcomes. Individuals

require personal and practical needs to be met in each

interpersonal encounter, and often respond negatively when one or both of these

types of needs are not met; unfortunately, many have a limited understanding of

how to resolve successfully this kind of conflict.

The information and recommendations detailed in this report

identify the importance of incorporating an emotional intelligence curriculum

into an organization’s existing training and development program to enhance

understanding, tolerance, and communicative effectiveness throughout the

organization. While many believe emotions do not belong in a professional

setting, emotional intelligence is a critical element in human relations

because it improves team acumen, enhances the conflict resolution process, and

promotes cross-cultural and multi-generational understanding.

Scope of the Report

The research of this report examines a) the definition of

emotional intelligence (EI), b) the effect of human emotion in the workplace,

c) the risks associated with ignoring EI, and d) the benefits of developing

both EI understanding and skill. This report provides general data and

information obtained from human resource professionals as to the amount of time

spent in dealing with emotionally charged situations and how improved EI can

enhance employee engagement and customer satisfaction. However, this research

does not supply a universal solution to interpersonal or behavioral issues, but

provides an alternative approach and additional tools meant to promote positive

conflict resolution.

Sources and Methods

of Data Collection

The information included in this report was derived from

both primary and secondary sources. Behavioral, psychological, and business

statistical data was gathered to establish the risks and benefits associated

with EI. In addition to reviewing academic and professional publications, seven

Insperity human resource specialists (serving more than 500 worksite employees

each) were surveyed to identify current trends and customer service practices

in dealing with clients and their staff.

Human Resource

Specialist Survey

Corporate executives strive to increase profitability, and

rely on employees to perform specific tasks in unison to achieve strategic

goals effectively and efficiently. To increase productivity, the company

organizes individuals into groups designed to maximize proficiency. The highest

performing workgroups are teams that function cohesively through cross-function

and multi-directional communication. This enhanced level of interaction allows

the team to identify obstacles, find solutions, and share best practices.

According to Harris and Sherblom, it is the team itself and not its leadership

that controls the group process (2008). Human resource (HR) departments assist

these groups in maintaining multi-directional communication, productivity, and

a work environment free from harassment.

However, this level of interconnectivity is not without its

challenges. In any interpersonal exchange, there are certain human needs that

must be met such as respect, empathy, and so on. When these

expectations are not met, negative

emotions are often triggered (Reeve, 2009). According to a recent survey of

human resource professionals, as much as 75% of their time is spent defusing

situations that have been complicated by emotions resulting in fight (e.g. dictating or venting) and flight (e.g. accommodating or avoiding)

stress behaviors. Without the knowledge necessary to develop skills to deal

with fear, disappointment, frustration, and anger, these confrontations can

escalate causing damaged relationships, diminished morale, and poor

performance.

However, this level of interconnectivity is not without its

challenges. In any interpersonal exchange, there are certain human needs that

must be met such as respect, empathy, and so on. When these

expectations are not met, negative

emotions are often triggered (Reeve, 2009). According to a recent survey of

human resource professionals, as much as 75% of their time is spent defusing

situations that have been complicated by emotions resulting in fight (e.g. dictating or venting) and flight (e.g. accommodating or avoiding)

stress behaviors. Without the knowledge necessary to develop skills to deal

with fear, disappointment, frustration, and anger, these confrontations can

escalate causing damaged relationships, diminished morale, and poor

performance.

The HR specialists surveyed average more than 10 years’

experience in dealing with workplace disagreements and hostility, and support

more than 100 employers in Northern California. These professionals estimate

that less than 2% of their client base has had any training related to EI. The

current lack of EI skills limits the effectiveness of human resource’s conflict

resolution efforts, requiring the expenditure of more than 30 hours per day

with marginal outcomes (e.g. issues that frequently resurface). Unsatisfactory

resolution often affects human resource professionals, individual performers,

customers, and team viability.

The HR specialists surveyed average more than 10 years’

experience in dealing with workplace disagreements and hostility, and support

more than 100 employers in Northern California. These professionals estimate

that less than 2% of their client base has had any training related to EI. The

current lack of EI skills limits the effectiveness of human resource’s conflict

resolution efforts, requiring the expenditure of more than 30 hours per day

with marginal outcomes (e.g. issues that frequently resurface). Unsatisfactory

resolution often affects human resource professionals, individual performers,

customers, and team viability.

Business Risks of

Ignoring Emotional Intelligence

Annoyance, intolerance, confusion, anxiety, and

disappointment are emotions that are expressed both verbally and through

behavior. Just as a positive, proactive attitude can enhance a work

environment, negativity and passive-aggressive behavior can be

counterproductive. Unfortunately, this is not an area organizations tend to

invest development resources, which frequently results in low job satisfaction,

hostile work environments, and employee altercations.

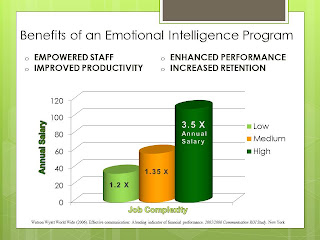

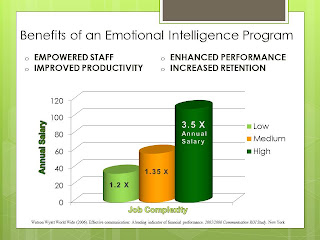

Reeve points out that expression

is how one communicates emotional experiences publicly to others (2009). When

employee frustrations are allowed to escalate (or intensify over time) the

communication process, relationship, team, and organization may be adversely

affected through reduced job satisfaction and employee turnover. Watson &

Wyatt estimate that organizations that experience excessive employee turnover

lose 10-15% productivity and spend more than three times the former employee’s

annual salary to replace a high performer in a complex role (2006). Therefore,

it is in the interest of key decision makers to invest in developing skills to

manage better emotions in the workplace.

Defining Emotional

Intelligence

“Emotions are internal events that coordinate many

psychological subsystems including physiological responses, cognitions, and

conscious awareness” (Mayer, Caruso,& Salovey, 2000, p. 1). The ability to

manage individual emotions is a skill that comes naturally to some, while

others seem to be ruled by feelings. Traditional management and professional

behavior dictates that emotions have no place in the work setting; yet the

ability to feel compassion, joy, and disappointment are human responses that

drive performance.

The question must then be asked whether emotion is

intelligence or an instinct. To be

considered a legitimate intelligence requires a) the ability to be

operationalized, b) a unique variance, and c) the ability should develop over

time. Human emotions meet these criteria as they can be employed in useful

purpose, vary significantly (both by event and individual), and are learned

through experience. For example, Jandt observes the more experiences one has

increases his or her social skills (2010). Therefore, the term “emotional intelligence” (EI) refers to

one’s ability to recognize proactively and understand emotions in self and

others, and to leverage this ability to apply reason to motivate, resolve

conflicts, or problem-solve. Armstrong points out that one’s emotional

awareness can be enhanced just as any other form of intelligence such as word, kinesthetic, spatial, or math and logic(2009).

Learning Emotional

Intelligence

Emotional intelligence development programs typically run

from a few hours to an entire day and cost relatively little in materials,

especially when compared with the long-term return on this investment. Mayer et

al. (2000), identify four basic skills that require development for emotional

intelligence a) reflectively regulating emotions, b) understanding emotions, c)

assimilating emotion in thought, and d) perceiving and expressing emotion.

Adult learning organizations, such as SkillSoft, the American Managers

Association, and Developmental Dimensions International (DDI), use similar formats

for their individual EI programs.

EI courses are typically broken into segments following a

brief self-assessment that can be applied online or in person. The intent of

the assessment is to help the participant inventory his or her current skill

set and behavioral tendencies before introducing tools. The core content of EI

classes explores body language and tone as potential emotional triggers.

Because the non-verbal portion of communication makes up more than 90% of

face-to-face conversations, it is important to understand and interpret

expressions and voice inflection (Mehrabian, 1984). Another common element of

the program identifies the methods in which one interprets and manages internal

assumptions (or stories), in an effort to keep those judgments or prejudices

from influencing individual responses.

The course is not an indication of one’s job performance,

abilities, or personal aptitude for success. The skills discussed throughout

the course are often common practices individuals ignore or forget to employ

before allowing themselves to become emotionally compromised. The intended

outcome of an EI program is to increase one’s capability to listen actively,

assign meaning, and provide feedback upon which others can both hear and act.

Such skills would enable frontline staff to resolve conflicts without escalating

an issue to management, employee relations, or the human resources department.

Surveyed human resource specialists unanimously agree that such a program would

improve employee retention, communication effectiveness, employee behavior, and team morale, while allowing them more

time to serve other client needs.

Business Case

When one considers the amount of hours to be saved in the

human resource department alone makes a compelling case for EI training.

However, the benefits extend from increased customer satisfaction scores, to

improved team performance, higher staff retention, and increased employee

engagement. According to Watson Wyatt Worldwide, companies with high employee

engagement enjoy 19% higher market share, 57% greater shareholder returns, and

higher productivity. Beyond corporate mission, vision, and values statements,

individuals looking to invest in a company are encouraged to consider the

business’ ability to retain key staff, use creative problem solving skills, and

establish a reputation as a good place to work.

When one considers the amount of hours to be saved in the

human resource department alone makes a compelling case for EI training.

However, the benefits extend from increased customer satisfaction scores, to

improved team performance, higher staff retention, and increased employee

engagement. According to Watson Wyatt Worldwide, companies with high employee

engagement enjoy 19% higher market share, 57% greater shareholder returns, and

higher productivity. Beyond corporate mission, vision, and values statements,

individuals looking to invest in a company are encouraged to consider the

business’ ability to retain key staff, use creative problem solving skills, and

establish a reputation as a good place to work.

Conclusions and

Recommendations

In addition to developing a client team’s ability to sell,

think strategically, lead, and communicate, there is a financial and

environmental benefit to increasing a workforce’s capacity to deal with

emotions effectively. Employees who manage emotion well tend to communicate

more efficiently and readily resolve conflicts with internal or external

customers. Organizations that communicate proficiently enjoy greater market

share, lower employee turnover, and higher productivity than competitors do,

while others may spend as much as 3.5 times an employee’s annual salary to

replace him or her (Watson Wyatt, 2006). Because EI may not provide immediate,

tangible benefits, many believe emotions should not be addressed in a

professional setting; however, a team’s emotional intelligence improves

communication, promotes collaboration, and is critical to organizational

success.

Reference

Harris, T. E.,& Sherblom, J. C. (2008). Small group and team communication (4th,

Ed.). New York; Pearson Education, Inc.

Jandt, F. E. (2010). An introduction to intercultural

communication: Identities in a global

community (6th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D. R., & Salovey, P. (2000). Emotional intelligence meets traditional

standards for an intelligence. Retrived on August 26, 2012, from:

http://www. unh.edu/emotional

intelligence/EI%20Assets/Reprints...EI%20Proper/EI1999Mayer

CarusoSaloveyIntelligence.pdf

Mehrabian, A., (1981). Silent

Messages: Implicit communication of emotions and attitudes (2nded.).

Belmont, CA: Wadsworth

Reeve, J. (2009). Understanding

motivation and emotion (5th Ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley &

Sons, Inc.

Watson Wyatt Worldwide, (2006). Effective communication: a leading

indicator of financial performance. Washington DC, USA: Watson Wyatt.

In

1936, the U.S. Patent office granted George Blaisdell (b. 1895, d. 1978) patent

number 2032695 for his “Windproof”

lighter. The approximate dimensions of the basic model closed are a) Height

2-inch, b) Width 1-inch, and c) Depth ½-inch (Unknown, 2012). The approximate weight is 2.05 oz. dry

(Unknown, 2012). Each Zippo lighter comes with a lifetime warranty.

In

1936, the U.S. Patent office granted George Blaisdell (b. 1895, d. 1978) patent

number 2032695 for his “Windproof”

lighter. The approximate dimensions of the basic model closed are a) Height

2-inch, b) Width 1-inch, and c) Depth ½-inch (Unknown, 2012). The approximate weight is 2.05 oz. dry

(Unknown, 2012). Each Zippo lighter comes with a lifetime warranty.